Rules for Startups Raising Capital in the Midwest – Part 6: Deal Terms

Note: “Rules for Startups Raising Capital in the Midwest” is a multi-part Entrepreneur Toolkit series based on Rev1 Ventures Capital Access Learning Lab. We suggest you review the preceding sections: Part 1 – Basic Information on Venture Capital, Part 2 – Capital Planning Worksheet, Part 3 – Building Your Investor List, Part 4 – Due Diligence, and Part 5 – Investor Outreach.

–

After months of courting investors and more months of due diligence, your Series A round is finally underway. The time has come to draft the terms. You are about to enter the most important discussions of your company’s brief history.

Series A terms determine the percent of the venture that the entrepreneur gives up, how much control investors have over future decisions, and, perhaps as importantly, this negotiation process sets the tone for the entire future relationship between you and your investors.

Fact vs. Fiction on Deal Terms

No two Series A deals are precisely the same. However, the more an entrepreneur understands the process and the realities, the more successful the outcome of any particular deal discussions will be.

Fact and fiction are more nuanced.

- Venture Capitalists want as much ownership as possible. Not really. Venture Capitalists’ share of the company will be based on the valuation and amount of capital raised, not on how much of the business they control. Assuming there are co-investors, VCs will typically insist on at least 20 to 25 percent of early-stage companies, which will bring the total share to 40 to fifty percent

- Entrepreneurs should raise capital at as high a valuation as possible. Not necessarily. The correct valuation is the valuation that yields enough money to build the business. The higher the Series A valuation, the higher the bar for revenue growth. When a startup strikes a deal that sets a bar too high to achieve, the company misses milestones. As a result, initial investors may decline follow-on rounds. That sends the wrong signal to new investors.

- Entrepreneurs want to raise as much capital as possible. Match the capital raise with the funds required (with a contingency) to meet the next set of company milestones.

- Entrepreneurs should take the first term sheet they can get. Often this is the case, but not always. However, if you have done the right job of targeting the right investor and building a relationship based on a shared vision for your company, the first term sheet can be the right one—and most likely, the only one. While there may some negotiation, remember that potential investors learned everything there is to know about the company during due diligence. So, while there may be some room for discussion, for the most part, the deal they propose is likely the deal.

Convertible Debt vs. Equity Rounds

Convertible debt is a debt instrument often used by seed investors with a maturity and interest rates. Convertible debt is structured as a loan intended to convert into equity at a specific milestone, NOT to be repaid. Thus, using convertible notes moves the complex discussion of startup valuation to the next round of financing.

The convertible note will likely carry an above-market interest rate considering the early-stage noteholder’s increased risk. In addition, if the startup company lacks the cash flow to make quarterly payments, there may be provisions for the interest to accrue until the next funding event.

There are many possible terms in a convertible note. The two most important are the valuation cap, which is the maximum valuation that shares could convert to, and the conversion discount rate. The discount rate allows the investor, at the next round, to convert the principal and accrued interest of the convertible debt into shares of stock at a discount.

In equity rounds, investors purchase ownership shares in a company at a set price (value) per share. Founders and employees generally own common stock, while investors generally own preferred stock.

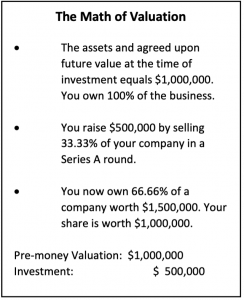

The valuation of the venture has two components before the investment (called pre-money)—the existing or current value and the imputed future value of the enterprise. The pre-money plus the investment equals the post-money valuation. Ownership percentages are determined by dividing each party’s investment by the post-money valuation.

Getting Down to Negotiations

Successful entrepreneurs develop realistic expectations of investment terms. In Series A, you will sell part of your ownership stake to third-party venture capitalists. You will be held accountable to generate a return on the investment—for yourself, your team, and most of all, your investors. You are no longer your boss. You will be accountable to the Board of Directors and investors, whether they sit on the board and not. If these realities don’t fit with your expectations, then you might not be the right leader for a venture-funded growth business.

Any entrepreneur who chooses to proceed with VC funding should engage qualified and experienced legal counsel to advise and represent them in negotiations. Ask for references and choose counsel that is a cultural fit with your company. This is the start of a meaningful relationship that you will want to build on over time, not only for the Series A round but for any subsequent funding rounds.

Counsel will advise you on using the capitalization (cap) table, a model that shows the pro forma ownership in your company, to evaluate the impact of the terms under negotiation on the percentages of ownership. Savvy legal advisors will analyze investors’ valuation of your business to understand how it was determined, explain it to you in terms that you know, and then teach you how to talk about valuation with potential investors.

That deep dive will detail everything from your company’s milestone commitments to market comps to percentages of ownership and dilution considerations. Many entrepreneurs believe that the company will generate the cash the business needs to grow after first-round funding.

Experienced legal advisors know that most ventures, whether they are immediately profitable or not (most aren’t), need subsequent investment rounds to scale up in three to five years. They understand that an entrepreneur’s percentage of ownership is likely to decrease over time. They make sure that an entrepreneur understands that, too.

Common Goals and Understanding Creates Smoother Negotiations and Builds Constructive Relationships.

Entrepreneurs will be better prepared to value their companies after considering valuation from the investors’ point of view. Drop any belief that investors love risk. They don’t. They love returns. They know that your company, like most entrepreneurial ventures, is likely to need more time and funding than you expect. Listen to them and learn.

The relationship between investors and entrepreneurs is all about long-term trust. When relationships begin with two-way trust, the company, the team, and the investors all benefit, especially when the business hits a rough patch, as it inevitably will.

More from Rev1 Venture’s Entrepreneur Toolkit

Checklist: 14 Red Flags Every Investor Looks For

Sources of Capital for High-Growth Companies